'Cause I'm a Medievalist Baby!

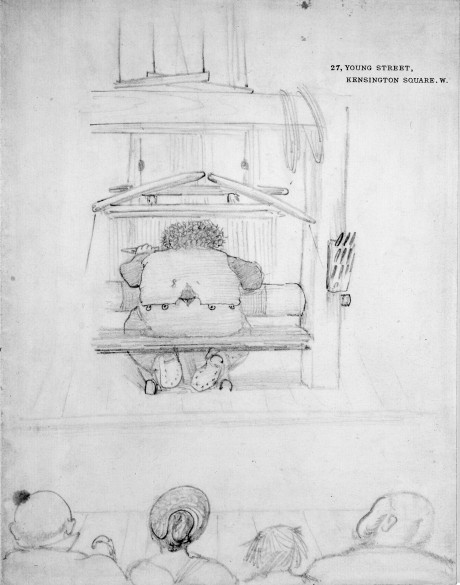

Morris and the Arts & Crafts movement was foregrounded by the writings of John Ruskin, who saw the Medieval period as a simpler and more straightforward time for the craftsperson. A furniture piece such as The Backgammon Players, created in 1861 demonstrates this interest in Medievalism. Morris collaborated with Edward Burne-Jones on the object, providing the concept with Buren-Jones providing the painted figures, fittingly in Medieval costume. It is thus fitting that in Beerbohm's illustration that the two men sit on a medievalist bench that they presumably designed.

Touching Me, Touching You

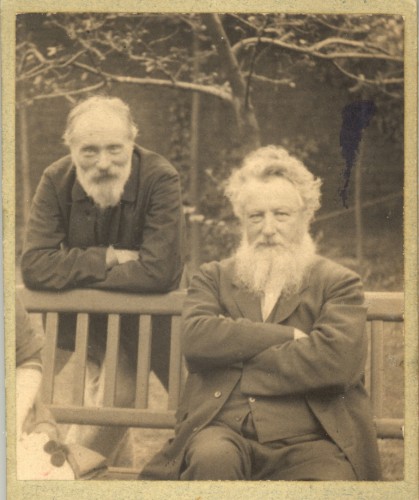

That Morris takes up the greater portion of the bench, relegating the slim Burne-Jones to one side communicates a sense that Morris had a “big” or possibly dominating presence. Edward Burne-Jones also made drawings of himself and Morris and it seems that he used his sketches to contemplate the stereotypes attached to their public personas. Burne-Jones too characterizes himself as a waif, in contrast to Morris’ fleshy and energetic presence.

Which Morris?

Morris was not just a leader and figurehead of the Arts & Crafts movement. In his later years he was an active socialist and throughout his life he wrote poems and fantastical short fictional stories. Because his disciplines were so varied, when discussing Morris in any sort of public discourse one had to specify which Morris he or she was referring.

Sir Max Beerbohm's cartoon of William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, published in the early 1900s. University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books Library.

Who’s looking?

This image is featured in a book of cartoons published in the early 1900s by Sir Max Beerbohm, entitled Rossetti and His Circle. Viewers of this plate illustration would have been readers of the book—that is, individuals who would have also been interested in Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his circle of fellow Pre-Raphaelite artists and designers. A secondary pair of eyes are those of Beerbohm himself, who was fascinated by Rossetti and his contemporaries, though the University of Cincinnati’s Archives and Rare Books Library asserts that it is not likely that the two men ever met. 1 The collection of cartoons also features images of Christina Rossetti, John Ruskin, John Millais, Oscar Wilde, and Elizabeth Siddal.

Why does this image matter?

This image is of interest precisely because William Morris is featured as a periphery character, rather than the star and hero of the craft narrative. It is also an image effectively built on the perceptions of an outside admirer and the collection of images thus appear both simplified and heightened. The book was not so much an instructive tool as an indexical device to highlight cultural perceptions and stereotypes. There is a sense of an inside-joke—for instance, Morris crowding the bench—that would be understood by those “in the know.” The element of an in-circle is further exemplified by the in text caption for the illustration that reads: “Topsy and Ned Jones, settled in the Settle in Red Lion Square.”2 Topsy, the nickname given to Morris, refers to a character in Uncle Tom’s Cabin who had wildly curly hair.3

Citing the Source: Craftsperson in Conversation

“So we will stick to our word, which means a change of the basis of society; it may frighten people, but it will at least warn them that there is something to be frightened about, which will be no less dangerous for being ignored; and also it may encourage some people, and will mean to them at least not a fear, but a hope.”

William Morris, “Signs of Change,” 1888.4

The bulk of Morris’ body in Beerbohm’s cartoon as well as Edward Burne-Jones’ drawing of Morris performing a weaving demonstration, both convey an essential solidity in character and communicate a heightened sense of girth. It seems that both Beerbohm and Burne-Jones are thinking through how to articulate the working body of a craftsperson. Though rather than depicting a craft act, both artists defer to Morris’ body. I would argue that the focus on Morris’ body was a device to argue for Morris as a fleshy, humanistic presence. The art historian Caroline Arscott asserts that this presence reverberated through his designs as “Morris produces a weave of life; his pattern does not amount to a two-dimensional diaper of flattened motifs…there is something fleshy about his design work” 5 She further argues that Morris does not merely create designs for surfaces; his designs have depth because they commune with his presence.6

In addition to his craft practices, Morris gave lectures on art and society, informed by his Socialist alignment, as well as wrote poems and short stories. Lectures such as “Signs of Change” reflect his utopianist commitment to the individual craftsperson as well as his hopes for a material revolution.

About William Morris (1834-1896)

As observed by the design historian, Pat Kirkham, William Morris was many things to many people.7 He met Edward Burne-Jones in 1853 while attending Oxford University and the two became close friends. Morris had entered university with the intention of becoming a clergy member but felt pulled in a different, more artistic and socially driven direction after reading John Ruskin’s “The Nature of the Gothic.” Ruskin’s text served as a guiding light to both Morris and Burne-Jones, who strove to put to practice Ruskin’s theory that the free craftsperson working with his or her hands produced superior art. This goal put Morris on a path that led him to open Kelmscott Press, and later in his career served as an advisor to the South Kensington Museum in London. Though politics underwrote Morris’ conceptions of design and labor throughout his life, he officially became a socialist in the late 1880s. His lectures on art and society—driven by his unease with industrial production and imperialism—provided both the foundation and the scaffolding for global dissemination of the Arts & Crafts movement.

Sources:

Arscott, Caroline. William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: Interlacings. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008.

Bennett, Phillippa and Rosie Miles, eds. William Morris in the Twenty-First Century. Bern, Germany: International Academic Publishers, 2010.

Kirkham, Pat. “William Morris: A Life in Design.” In The Beauty of Life: William Morris and the Life of Designedited by Diane Wagonner, 20-31. London: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

Morris, William. Hopes and Fears for Art. London: Roberts Brothers, 1882.

Morris, William. Signs of Change. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1896.

Ruskin, John. The Nature of the Gothic: A Chapter of the Stones of Venice. Hammersmith: Kelmscott Press, 1892.

University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books Library. “Dante Gabriel Rossetti Cartoons.” Accessed May 2, 2019. http://digital.libraries.uc.edu/exhibits/arb/williamMorris/rossetti_cartoons.php

- “Dante Gabriel Rossetti Cartoons,” University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books Library, accessed May 2, 2019, http://digital.libraries.uc.edu/exhibits/arb/williamMorris/rossetti_cartoons.php.

- “Dante Gabriel Rossetti Cartoons,” University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books Library, accessed May 2, 2019.

- “Dante Gabriel Rossetti Cartoons,” University of Cincinnati Archives & Rare Books Library, accessed May 2, 2019.

- William Morris, Signs of Change (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1896), 2.

- Caroline Arscott, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones: Interlacings (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2008), 165.

- Arscott, William Morris and Edward Burne-Jones, 165.

- Kirkham, Pat. “William Morris: A Life in Design,” in The Beauty of Life: William Morris and the Life of Design, ed. Diane Wagonner (London: Thames & Hudson, 2003), 21.