Sloppy Craft

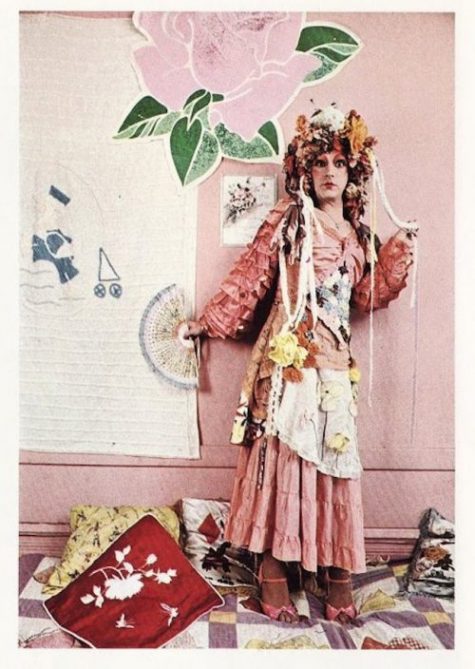

“Sloppy craft” was introduced to craft discourse in November 2007 in a conversation between Glenn Adamson and Anne Wilson at a symposium held at the Victoria and Albert Museum. The term identifies a conscious choice on behalf of the artist to utilize a “sloppy” aesthetic for rhetorical purpose. Though the term came forty years later, I would argue that its visual language existed in the 1970s with the California-based performing arts group, the Cockettes. Generally speaking, theirs was an aesthetic of excess through the textures of velvet, lace, satin, rhinestones, and studs. The art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson specifically points to the frayed hem of Andrews’ skirt as a site of sloppiness in the sense that the threads seem to “drip" Why be sloppy, though? In part it was surely due to the nature of how the Cockettes' costumes were acquired and pieced together. But it was also a way to communicate the hyperbole and freestyle nature of their lifestyle.

Beg, Steal, Borrow

The various components of Andrews’ ensemble would have been acquired from rigorous thrifting rituals conducted by the members of the Cockettes community all of whom lived together in San Francisco. It should also be noted that the group lived communally, pooling their food stamps and their clothing.

Camp Aesthetic

The makeshift and thrifted aesthetic of Andrews’ outfit speaks to a system of citation: the act of pulling together disparate items of clothing also gestures to an unseen source material. In other words, the sloppy craft aesthetic intersects with Susan Sontag’s 1964 conception of “camp,” that is, a material embrace of bad taste and the artificial. Camp, too, exists as a system of quotation, in this case, Andrews’ headdress may be referring to any number of non-Western sources. However, due to its assemblage, the “original” referent has become a hybridized object.

Performing On & Off Stage

What the Cockettes brought to the stage was their lived experience, in fact the remaining members describe the shift from street to stage as a natural spilling from one realm into the other. Though their performances became increasingly coordinated, the group maintained a flair of spontaneity and resistance to choreography. Art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson argues that they were not only performing for an audience, but for each other and themselves. But to carry this idea further, if the Cockettes rehearsed their lives on and offstage, what, then, was the act?

Photograph by Jerry Wainwright of Prissy Andrews, member of the performing arts group the Cockettes, 1974. Image (of the image) taken by the author.

Who’s looking?

This image appears in Alexandra Jacopetti’s 1974 text, Native Funk & Flash: An Emerging Folk Art, a book that identified and described sartorial and decorative trends in the 1960s-1970s. The viewer of this representation of Prissy would presumably have been a reader of the book, perhaps looking for inspiration for their own clothing and ornamentation or otherwise seeking out a souvenir from the period.

Though Native Funk & Flash is the result of the creative partnership between Jacopetti and photographer Jerry Wainwright, the project is driven by Jacopetti’s eyes. At the book’s outset she states her position as a maker, writing that the project “comes from my own point of view—as an observer of its emergence and development, as a folk artist, and as a participant in the culture from which it springs.”1 The text supplementing each image carries a conversational tone, as if Jacopetti is taking the reader on a friendly tour of San Francisco’s visual culture.

Why does this image matter?

Image (of the images) taken by author.

The issuing of this book comes two years after the dissolution of the Cockettes in 1972. Prissy Andrews is featured next to a photograph of fellow Cockette, Scrumbley, wearing a “performance suit” made up of doilies.2 That both performers are featured in this book signifies their popularity as fashionable figures in San Francisco’s Bay area while also demonstrating the extensiveness of their creativity.

On the page opposite to the performers, Jacopetti’s text notes that their assembled outfits are a demonstration of “costuming, not craftsmanship”3 And indeed, Andrews’ outfits are unique in a book that emphasizes folk embroidered interventions on clothing and accessories. Jacopetti’s efforts to document the material culture of her world render this book a valuable document for a particular moment (the 1970s) and a specific geographic locale (the Bay area). Additionally, the individuals featured are not merely unidentified models, but known community figures such as Scrumbley and Andrews.

Crafting Identity

Although Jacopetti distinguishes Prissy Andrews’ ensemble as costuming rather than craftsmanship, I stand with art historian Julia Bryan-Wilson who treats their sartorial constructions as significant craft efforts. As has been demonstrated by the highlighted areas in the above image, Andrews’ assemblage does more than clothe his/her body. This was a context in which clothes were treated as gender itself, essentially blurring the boundaries between costume and person. Bryan-Wilson quotes Cockette Fayetta Hauser, who reflects, “With my drag, I was collaging myself together.”4 Bryan-Wilson pushes this concept further when she asserts that “crafting drag was not about dissembling (or falsity) but about assembling an earnest, if provisional, self by which she could engage in a conversation with herself.”5 Drag craft, as it was activated within the Cockettes, was a means of legible assemblage that reflected an interior landscape; the performers’ clothes were effectively their skin.

Bryan-Wilson also notes that Jacopetti’s praise given to Andrews and Scrumbley for exhibiting a “disregard for skill” in their clothing loosely aligns them with a “countercultural politics of anti-commercialism and a rejection of mass production that would pave the way to living with more integrity.”6 In this way, the handmade world of the Cockettes seems to be a gender-nonconforming descendent of William Morris’ value in the individual craftsperson.

About Pristine Condition “Prissy” Andrews

Few specifics are known about Prissy Andrews, aside from Jacopetti’s caption, in which he/she remarks he/she worked her way up from Texas. The performing arts community to which Andrews belonged, the Cockettes, has received ample coverage. By the late 1960s, the Bay area was home to around 300 communes. The Cockettes was not the only group with an interest in costuming; the group’s pianist Peter Minton lived in a commune that cast an eye to the 1920s. The Cockette’s first show was at the Palace Theater on Halloween in 1969 when they performed a spontaneous kick line during the intermission for the Nocturnal Dream Show. The group produced vibrant performances for two and a half years before fracturing over disagreements about “going professional” and whether or not to have free shows. In the years that followed, many of the members succumbed to drug overdoses and later, HIV/AIDS. Nevertheless, their gender-bending craft practices are integral to San Francisco and the queer community writ large.

Sources:

Auther, Elissa and Adam Lerner, eds. West of Center: Art and the Counterculture Experiment in America. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Blauvelt, Andrew, ed. Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2015.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia. Fray. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017.

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” In The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader, edited by Amelia Jones, 392-402. New York and London: Routledge, 2003.

Edwards, Elizabeth and Janice Hart. Photographs, Objects, Histories: On the Materiality of Images. London and New York: Routledge, 2004.

Jacopetti, Alexandra. Native Funk & Flash: An Emerging Folk Art.San Francisco: Scrimshaw Press, 1974.

- Alexandra Jacopetti, Native Funk & Flash: An Emerging Folk Art (San Francisco: Scrimshaw Press, 1974), 5.

- Both ensembles were designed by Cockette Billy Bowers. So, maybe not so devoid of skill.

- Jacopetti, Native Funk & Flash, 5.

- Julia Bryan-Wilson, Fray (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 201), 63.

- Bryan-Wilson, Fray, 64.

- Bryan-Wilson, Fray, 66