Painting Pain

One of Kahlo's legs was rendered shorter than the other after she contracted polio at the age of six. Additionally, in 1925, when she was eighteen, Kahlo boarded a bus that was hit by a tramcar. The crash fractured her collarbone, spine, and foot, and a steel handrail passed through the left side of her body, puncturing her abdomen. The trauma of her accident and the enduring pain that it bore frequently appeared in Kahlo’s paintings. Throughout her life, Kahlo’s body remained central to her work not only because her pain was persistent, but also because she insisted that she was the subject that she knew the best.

Making Herself Up

The objects recovered at Casa Azul in 2004 has led to three exhibitions in Mexico City, London, and Brooklyn of Kahlo’s material culture. “Las apariencias engañan: Los Vestidos de Frida Kahlo/Appearances Can Be Deceiving: The Dresses of Frida Kahlo” reveals through objects the consciousness and care Kahlo exercised in constructing her identity. When out of bed, she used clothing to convey her heritage and political beliefs by wearing an embroidered blouse or huipil and a full-length skirt, or enagua—an ensemble originating from her mother’s region in Oaxaca. As indicated by Kahlo's drawing pictured above (and also recovered from Casa Azul), the combination of skirt and shirt also served to conceal the brace around her ribs and her withered leg.

The Personal Is Political

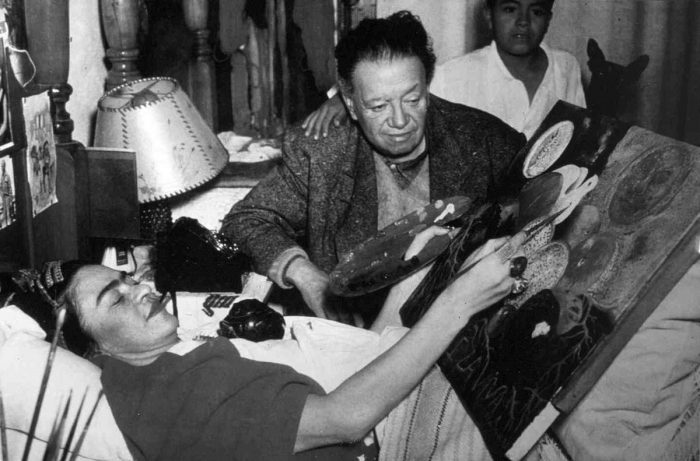

The pain Kahlo experienced in her personal life through her tumultuous marriage to Diego Rivera (featured at her bedside), as well as the ever-present pain residing in her body, proved to be a continuous fountain of material for her paintings. The pervasiveness of Kahlo’s legacy is due to the way in which the boundary between her lived experience and her painted life existed in near constant state of flux during her life and after her death. She was also unwavering in her identification to her indigenous heritage and her leftist politics. The presence of her hand in the craftsmanship of her identity continues to carry an enormous weight felt even in exhibitions of her treasured objects and clothes, divorced from her body.

Photographer unknown, Frida Kahlo painting Naturaleza Viva in bed with Diego Rivera at her bedside, 1952. fridakahlofans.com.

Who’s looking?

This appears to be a documentary photograph, with the intention of “looking natural” but reads as being a bit posed. Within the image both Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera direct their attention to Kahlo’s brush and the painted surface of her canvas. The painting “in progress,” Naturaleza Viva also appears to be in a finished state despite the perceptible paint on Kahlo’s palette. The finished painting somewhat undermines Kahlo and Rivera’s gazes; what process are they witnessing? This image, like the photographs of Yanagi, Leach, and Shoji as well as Art Carpenter, demonstrate the difficulty of capturing internal knowledge or emotion metamorphosizing into external material.

Why does this image matter?

Kahlo first began painting in bed after a bus/tram accident rendered her abject in 1925. Throughout her life she was frequently bed bound with her chest and abdomen encased in plaster. Between 1950-1952, when this photograph was taken, Kahlo endured several operations on her spinal column that proved to be especially debilitating.

That Kahlo is captured reclining in this photograph makes a statement about her disabled bodily state, even as she has clearly attended to her appearance by braiding her hair and adorning herself with pre-Columbian jewelry. Frida’s father was a portrait photographer and she had long-standing friendships with photographers such as Nikolas Muray and Gisèle Freund. This is all to say that not only was Kahlo photographed regularly, but she also knew how to pose.1 Frequently circulated images of Kahlo typically feature her with her chin up, effusing a feminist glamour. But this image, far from being the only photograph to picture Kahlo in bed, also seems to argue that despite being bedridden she refused to cede her identity as an active artist.

To What Extent Is Kahlo a “CraftsPerson”?

I would argue that Kahlo’s sense of individualism and self-determinism—made material in both her paintings as well as her sartorial choices—broadly identify her as a craftsperson, if not in practice then certainly in ideology. Kahlo made explicitly political choices in her dress—incorporating the huipil blouse and enagua skirt—actions that seem to echo a nationalistic spirit often woven through global iterations of the Arts & Crafts movement. Citing an allegiance to her mother’s region, Tehuantepec Isthmus in Oaxaca, Kahlo also seems to hybridize an idea of “native.” We may ask ourselves how this “native” differs from the “native” seen in John Lockwood Kipling’s drawing. For one thing, comparative literature scholar Alba F. Aragón asserts that “Kahlo turned to the clothing of her nation’s most traditionally downtrodden groups, both as a disabled person seeking the physical comfort afforded by indigenous garments and as an individual wanting the distinction of garments that were not mass produced.”2 In other words, Kahlo’s self-fashioning was motivated by politics that referred to a “native” body, but was also driven by the reality of her own bodily condition.

About Frida Kahlo (1907-1954)

Khalo’s indomitable spirit has been co-opted and commodified in popular feminist culture since the 1990s. Born to a German father and a European and indigenous-descended mother, Kahlo grew up in Coyocoán, Mexico City in her family’s Casa Azul. Kahlo became interested in politics at a young age, eventually joining the Mexican Communist Party in 1927. She spent the late 1920s and early 1930s traveling the United States and Mexico with her husband Diego Rivera. During this time, she began to formulate her own artistic style, mixing references to Mexican folk art, pre-Columbian, and Catholic mythology with scenes from her own biography. Her first solo exhibition, facilitated by the surrealist André Breton, was held in 1938 at the Julien Levy Gallery in New York City. The success of this exhibition led to another in Paris in the following year and throughout the 1940s, she exhibited regularly in the United States and Mexico. Kahlo’s work has often been grouped with surrealism and magical realism, but art historians have been contesting and complicating this categorization since the recovery of her work in the 1970s to the point that today Kahlo holds a category all her own.

Sources:

Aragón, Alba F. “Uninhabited Dresses: Frida Kahlo, From Icon of Mexico to Fashion Muse.” Fashion Theory18, no. 5 (November 2014): 517-550.

Blake, Kevin and Lis Pankl. “Made in Her Image: Frida Kahlo as Material Culture.” Material Culture 44, no. 2 (Fall 2012): 1-20.

Freund, Gisèle. Trans. by Elliott, Nicholas. Frida Kahlo: The Gisèle Freund Photographs. New York: Abrams, 2014.

Sekula, Allan. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39 (Winter 1986): 3-64.

Walker, Katri. “Las Apariencias Engañan: Los Vestidos de Frida Kahlo (Appearances Can Be Deceiving: The Dresses of Frida Kahlo).” West 86th 24, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2017): 294-297.

- Katri Walker, “Las Apariencias Engañan: Los Vestidos de Frida Kahlo (Appearances Can Be Deceiving: The Dresses of Frida Kahlo),” West 86th 24, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2017): 294.

- Alba F. Aragón, “Uninhabited Dresses: Frida Kahlo, From Icon of Mexico to Fashion Muse,” Fashion Theory 18, no. 5 (November 2014): 531.