The Hands Have It

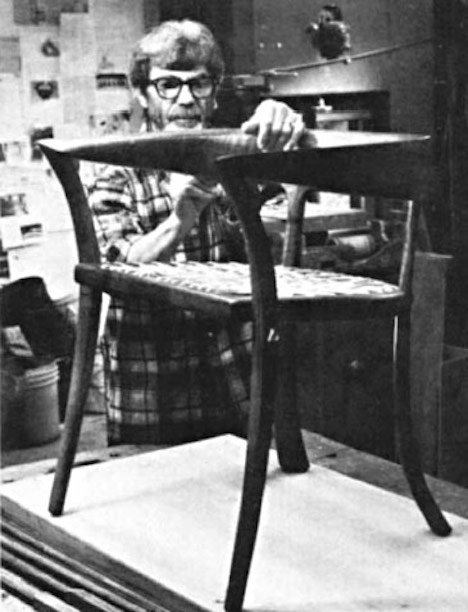

It is not clear what action Carpenter performs on the chair. This, combined with the quality of the photograph, work to shield the viewer’s eyes from the craft act. However, it is clear that Carpenter is making some kind of physical contact with his object. This cannot be an accident; rather, it overtly conveys the fact that Carpenter’s work has been made by his hands. I detect a posed quality in this photograph, perhaps due to the lack of clarity in Carpenter’s action, which only underlines the difficulty in capturing the transmission of an embodied knowledge.

The Object, Objectified

The finished “Captain’s chair” dominates the pictorial field. That the chair seems to screen Carpenter draws our attention to its presence, rather than that of its maker. By this measure, it also communicates a sense that Carpenter’s work speaks for him.

Photographer unknown, Art Carpenter in his Bolinas, California workshop, c.1982. Fine Woodworking Magazine.

Who’s looking?

There are two kinds of looking taking place in this photograph. Within the frame, Carpenter’s gaze is concentrated his making process. Outside the frame, the viewer looks at Carpenter looking at his chair. This image was featured as one of many supplements for a profile on Carpenter for the November/December 1982 issue of the Fine Woodworking magazine. The publication’s readership likely reflected their primary cover feature: a white, male woodworker.

Why does this image matter?

“I sometimes resent the lack of immediacy in wood, and wish it were clay that I could squish and re-form, or paint that I could splash on in one stroke and there it would be…Wood is a very bullheaded material.”

Art Carpenter, quoted by Rick Mastelli, 1982.1

This photograph has an almost archival purpose in the sense that it documents Carpenter at the conclusion of a making process. In the original spread, the photo to the left of this site’s featured photograph shows Carpenter standing approvingly beside his Captain’s chair in progress. The caption notes that the two photographs are two versions of the same chair taken seven months apart; taken together they record a sense of progression.

This series of photographs also stands in contrast to the 1952 image of Yanagi Soetsu around Bernard Leach clustered around Shoji Hamada because it shows a finished product. It offers the viewer a completed arc of making, an attempt to bridge their readership’s understanding of how Carpenter has transferred his knowledge from his body to a realized object.

Counter to the Culture

Rick Mastelli’s Fine Woodworking profile on Carpenter makes plain that the craftsman’s individualism functioned as a kind of activism; “Independence of thought requires independence of economics.”2 Carpenter’s individuality was communed onto the objects that he made in that he emphasized the handmade over the industrial.

In 1969, Carpenter met Thomas D’Onofrio, then a Ph.D. student at the University of California-Berkley on a quest to find an alternative and more fulfilling way of living. Carpenter took D’Onofrio on as an apprentice. The experience so profoundly transformed D’Onofrio that he burned his university papers and instead began a network of workshops in 1972 for various crafts that operated as the Baulines Craft Guild. By 1976 D’Onofrio had produced a master’s thesis entitled, “Craftsmanship and the Quest for Self-Discovery” based on his experiences with the Guild’s educational system. Crucially, the Guild incorporated key principles from D’Onofrio’s apprenticeship with Carpenter, chiefly that “The way for creative social change is through the emancipation of individual consciousness”3 Although Carpenter played into the mythic cultural identity of the craftsperson—that is, his ideology of self-determinism—he was also quite conscious that the lifestyle of the craftsperson was radical in its simplicity and tenuous in its financial sustainability.

About Art Carpenter (1920-2006)

Art Espenet Carpenter did not move to San Francisco until 1948 when he was 28. Born in New York City, Carpenter attended Dartmouth College where he studied economics with the intention of becoming an accountant. He then served four years in the Navy in World War II. In 1947, back in New York City, he attended a design exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art where he encountered a bowl made by James Prestini. The simplicity and functionality of the object moved him to rethink his career as a manufacturer for the middle class. Recalling how pleasant San Francisco had been when he had visited on shore leave, he headed west and bought a lathe. Carpenter developed several trademarks for which he became well known including the California Round-over style, the Wishbone Chair, and the Band-sawn drawer. Throughout his career, Carpenter maintained four basic criteria for “good design”: function, durability, simplicity, and practicality.4

Sources:

Auther, Elissa and Adam Lerner, eds. West of Center: Art and the Counterculture Experiment in America. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Blauvelt, Andrew, ed.Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia. Minneapolis: Walker Art Center, 2015.

D’Onofrio, Thomas. Craftsmanship and the Quest for Self-Discovery. M.A. Thesis, University of California Berkeley, 1976.

Douglas, Mary. “The Craftsman as Yeoman: Myth and Cultural Identity in American Craft.” In The Haystack Reader: Collected Essays on Craft, edited by the Haystack Mountain School of Crafts, 71-86. Orono, ME: University of Maine Press, 2010.

Koplos, Janet and Bruce Metcalf. Makers: A History of American Studio Artists. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

Mastelli, Rick. “Art Carpenter: The Independent Spirit of the Baulines Craftsman’s Guild.”Fine Woodworking, no. 37 (November/December 1982): 62-68.

Williamson, Scott Graham. The American Craftsman. New York: Crown Publishers, 1940.

- Rick Mastelli,“Art Carpenter: The Independent Spirit of the Baulines Craftsman’s Guild,” Fine Woodworking, no. 37 (November/December 1982): 66.

- Mastelli, “Art Carpenter”: 65.

- Thomas D’Onofrio, Craftsmanship and the Quest for Self-Discovery (M.A. Thesis, University of California Berkeley, 1976) 8.

- Janet Koplos and Bruce Metcalf, Makers: A History of American Studio Artists (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2010), 289.